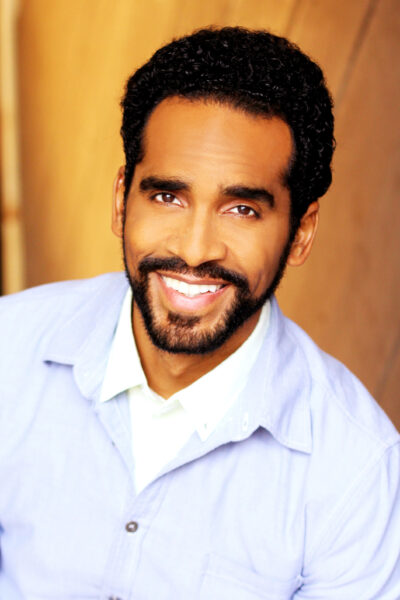

Spencer Britten was just a year out of graduate school when he announced his intentions to the opera world. At an industry audition at the Glimmerglass Festival, the Rossini tenor performed “Ah! Mes Amis” from La fille du régiment.

The aria, which requires a tenor to land nine high C’s in close succession, occupies its own rung as a bona fide showstopper. A young Luciano Pavarotti used it in 1972 as the exclamation point to his first-ever performance at the Metropolitan Opera, thrilling the house by holding out the final C for nine seconds.

In 2007 at La Scala, an audience urged Juan Diego Flórez to an immediate encore, breaking a tacit no-no that had lasted three-quarters of a century. The same thing happened at the Met in February 2019, when after several minutes of applause a director gave Javier Camarena the nod to sing Tonio’s jubilant aria one more time.

When Britten took the stage, “He sang the aria and interpolated high D’s to it, which nobody does,” said Miguel Rodriguez, president of Athlone Artists, who was in the seats. “That blew my mind away!”

A year and a half later, the tenore contraltino is still getting used to the pace his talent has created. He’s won multiple grants and fellowships, contests and roles. When opera isn’t filling up his calendar, a solo concert gig is around the corner. And that is only part of the story.

At that same festival, Britten landed a role in West Side Story. Choreographer Julio Monge, who had worked under Tony-winning choreographer Jerome Robbins for years, passed on that knowledge to Glimmerglass dancers.

Britten had grown up with dance. He studied contemporary and jazz with choreographer Cori Caulfield and ballet with Royal Academy of Dance instructor Isabelle Yuan, both of whom had taught students who went on to major companies; and tap with Van “The Man” Porter, one of the most innovative tap dancers of the 1990s. Britten’s role as Gee-tar, one of the Jets, included work as a featured dance soloist.

“It was incredible,” he said, “one of the most special shows I’ve been a part of.”

So good, it reminded Britten, who had gravitated toward opera exclusively, of how much he still needed dance.

“West Side Story really kicked me back into dance shape, and into the mentality that I should still be dancing,” he said. “I’ve been really focusing on making sure that that aspect of my training is being fed as well as my singing.”

A 2019 role also paid unexpected dividends. Britten played the lovestruck Leon in The Ghosts of Versailles, a 1991 opera by John Corigliano. Because the show was a co-production between Glimmerglass and the Royal Opera of Versailles, he reprised the role in December at the Palace of Versailles and served as dance captain in the production.

He has always lived between worlds. He is influenced both by the English lineage (he’s a fifth cousin of composer Benjamin Britten) and maternal Chinese grandparents who influenced him growing up in Port Moody, British Columbia.

“So I have a lot of Chinese culture in my lifestyle and in my blood,” he said. “I’m very proud of both my heritages.”

He started dancing at age 6, after seeing his sister dance and deciding that was something he wanted to do. A boys choir followed at 7, which led to voice lessons. He began dreaming of Broadway in middle school and high school, when Billy Elliott the Musical and The Book of Mormon were taking home Tonys.

Those very dreams ended up leading him in a different direction. Britten’s ballet studies were deepening an appreciation for the music the dance expressed. At the same time, his high school voice teacher, Gina Oh, noticed an aptitude that ran deeper than showbiz and started slipping arias and art songs into his repertoire.

“She’d say, “‘Oh, just try this, I think it would be fun and good for you,’” Britten said.

He didn’t realize it then, he now says, but Oh was building his audition package for college, one broader than musical theater alone. Another contender – opera – had muscled its way into the mix.

It came time to choose. Between theater, dance and opera studies, which way would he go? He applied to three different colleges with strong programs in each major and was accepted into all three.

“My gut told me to go with the opera program, even though I was so focused on musical theater,” he said. “And the more I studied and learned about opera, the more and more I fell in love with it.”

The attraction appears mutual. In his first couple of years working professionally, the Vancouver and Montréal opera communities have rewarded him with grants and scholarships. He won young artist fellowships at Glimmerglass and was a finalist in the Neue Stimmen International Voice Competition in Gütersloh, Germany.

“I am over the moon at this point in my career,” he said. “I still feel like I’m very young and super eager. But I’m so fortunate I have been given so many opportunities. Because of things like Glimmerglass, I have the opportunities to do opera and throw some musical theater in there.

“And though Broadway isn’t my primary focus at this point in my career, I’m still able to incorporate that into the work I do, which is really nice. And I found that that history in the work I do in musical theater and dance is valued by opera companies as well.”

Two years out of graduate school, he’s had time to reflect on the contrast between dreams that come true and everyday life.

“I’m a really big proponent of trying to show the world that opera singers are just regular people,” he said. “Everybody looks at it like it’s such a posh life. But really, we just come to work. We often go for a beer after work just like a lot of other people. We get to travel a lot, which can seem glamorous, but it can be really grueling as well. And that’s why you see a lot of people drop out of young artist programs or school because the lifestyle itself is very difficult. And that is a shock. But it’s something I’ve been fighting through, and it’s been an exciting journey.”

He’s grateful for a circle of friends whose opinions he values on anything from choice of repertoire to potential bookings or just when to take a break.

“It’s really important to have those people you can rely on to tell you what’s good and what’s not. Especially when you’re just go-go-go all the time.”

At the same time, he knows peace of mind must come from within. A photo on his Instagram shows his own hand holding a self-help book open to a chapter about “the importance of saying no.”

“That topic in particular is something that I grew up not even realizing I needed to battle,” Britten said. “There was a constant need to please people. And over the past couple of years, what I’ve found with this art form is that you really can’t please everyone and that setting those boundaries is what’s going to give you longevity.”

Based in Montréal, he enjoys cooking or eating sushi with his partner, opera singer Ian Burns, balancing yoga and the gym or taking the occasional dance class or workshop.

He’s in his second season with L’Atelier Lyrique de l’Opéra de Montréal, but could imagine relocating to another city, if he could find the right one. For now home is good, and sometimes better than good.

In October he was the tenor soloist in the Lyric Opera’s performance of Carmina Burana, navigating among other things the counterintuitive sing-songy cliffs and valleys of a doomed goose before the feast. Meanwhile, 40 dancers from Les Grands Ballet drew themselves or were pulled toward the center of a wheel of destiny, a circle overhanging the stage, a “cycle of existence” made up of joy, bitterness, worry and hope — a resolution of sorts for all of the choices and chance circumstances that had led him to the Salle Wilfrid-Pelletier before 2,500 people.

“It was really incredible to see my whole world come together with the dance and the opera kind of fused into one,” he said. “It was a really a special moment for me. The production was so well received, and the dancers were incredible. It was an incredible energy. That’s going to be a highlight for a long time.”

– Andrew Meacham