On Feb. 22, 1980, a team of young amateur hockey players exceeded expectations, reaching the gold medal game in the Winter Olympics, where their luck was supposed to run out.

The Americans, one of the youngest teams ever assembled, had few players who had even cracked the minor leagues. The Soviets were nearly all professional players and four-time defending gold medalists. The United States won, 4-3, one of the greatest upsets in sports history, a game with its own nickname, the “Miracle on Ice.”

Eric Fennell, then 7, was watching on television in Allentown, Penn. The boy fell instantly in love with a sport he had never played. He hadn’t even skated much, apart from on a frozen canal near the house he grew up in, but not long after that Miracle on Ice, Fennell joined his first hockey league.

Another 12 or 13 years would pass before another chance event led him to the discovery of his life — his own voice.

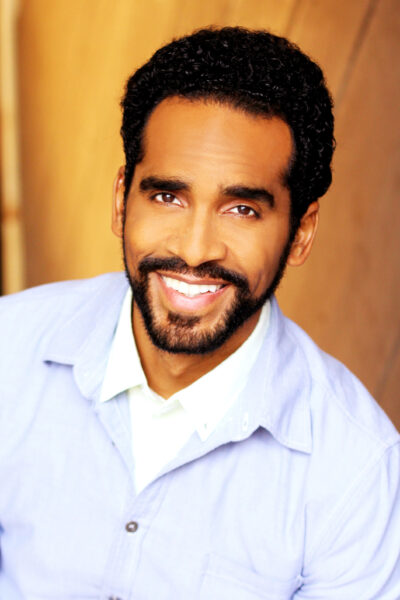

“It does feel a little like fate, absolutely,” Fennell said. When we spoke by phone, the lyric tenor was rehearsing his lead role as the Earl of Leicester in Odyssey Opera’s production of Rossini’s Elisabetta, Regina d’Inghilterra (March 13 and 15 in Boston, Mass.), the latest in a long string of robust romantic roles.

He has played title roles in Werther, Roméo et Juliette and The Tales of Hoffmann; the Duke in Rigoletto, Pinkerton in Madama Butterfly and on and on. Critics have praised his fearless high register and emotional depths; his concert work in Beethoven’s 9th Symphony and the requiems of Verdi and Mozart alone have taken him to top concert halls across the United States and abroad.

In what might be the happiest coincidence of many, Fennell’s musician parents never pressured him to follow their career paths. They just surrounded him with music, teaching him to read notes before it was necessary to read words.

Nor did they discourage his sports. Eric’s skills as a defenseman improved; he made the Philadelphia Jr. Flyers, an elite proving ground for future college players and beyond.

By high school, Fennell was playing the trumpet and singing in the choir. The hockey team also demanded more time, money and travel to away games. So, his father George, who plays French horn with the Marine Band of Allentown, made his son an offer: Keep music in his life, and he would underwrite the costs of playing.

“I guess he didn’t want me to become a total jock,” Fennell said. “He wanted to keep me sort of well rounded.”

As a senior, he tried out for his first musical, winning the role of Conrad Birdie in Bye, Bye, Birdie. “There was a girl I liked who was in it,” he said.

He played Division III hockey for Gettysburg College all four years, serving as captain his senior year. At a pickup basketball game his sophomore year, he met Viennese student Alex Puhrer who introduced him to opera.

“This guy had three or four milk crates full of CDs of operas. I never knew anything about opera. I had never met an opera singer. I was not connected with that side of the world.”

He was impressed. “For me it didn’t resemble any other kind of artistic genre that I knew,” he said. “I connected with it because I viewed opera singers as doing something very athletic.”

At 20, he had his first voice lesson. His teacher, Kermit Finstad, encouraged him to “breathe low” and create support in his body. By the end of that first session, he said, “This voice came out of me that I didn’t even know was in there.”

He changed his major to music, earning a master’s after graduation from Boston University. Apprenticeships with the Chautauqua and the Seattle Opera followed. He was covering the role of Rodolfo in La Bohème for Glimmerglass Opera in 2000 when the principal canceled his final two shows and Fennell jumped in; from there he never looked back.

He’s lived in Berlin, Germany for a decade now, a city with three opera houses and good flight connections both to gigs in Europe and his parents in Pennsylvania. He draws inspiration from hockey, the commitment to go after the money notes.

“When people go to the opera, they don’t go to hear the tenors sing the low notes,” Fennell said. “They go to hear them sing the high notes. Everyone’s sort of waiting for the high note at the end of ‘La donna è mobile’ (Rigoletto), or ‘Che gelida manina’ in La Bohème, or in ‘Nessun dorma’ in Turandot.”

The payoff is richer than money. Fennell has felt that way since he first discovered opera.

“When you find the thing that you love, it’s hard work but it doesn’t feel like work,” he said. “You put in hours and hours of work and you’re still enjoying working on it. I think I’d been looking for that all my life until then. And I felt like I had finally found it.”

He’s keeping up with his first love, too, in what’s known as a “hobby team” in Berlin. The kind of league where everyone still wants to win badly, but it’s okay to stop short of getting hurt.

“I couldn’t blow my knee out,” he said. “My agent wouldn’t like that.”

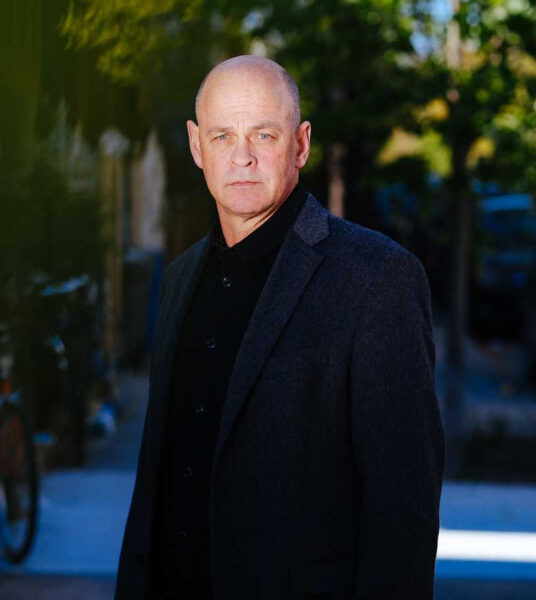

— Andrew Meacham