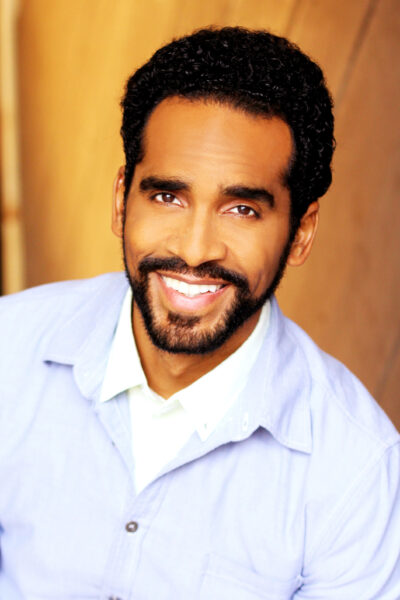

In so many ways, Mark Shapiro is an all-of-the-above kind of artist. By defying the idea of a niche, he has expanded his own world and that of those who have worked with him.

“I think the way I’ve always tried to brand myself is as a nonspecialist,” said Shapiro. “If you do early music, that informs your understanding of a piece that was written yesterday, and vice versa.”

Looking for those opportunities, he said, is “the opposite of a specialist.”

He was preparing to conduct a concert with the Prince Edward Island Symphony Orchestra when we spoke by phone. As PEI’s music director, Shapiro designed the concert to lead off with The Planets, by Gustav Holst; then come back after intermission with The Hockey Sweater, a popular 2011 Canadian piece by Abigail Richardson-Schulte based on a story by Roch Carrier, which uses hockey sticks and music scores themselves as percussion instruments.

He enjoys pairing pieces from the classical repertoire like Mahler with “what we call a ‘roots artist,’ an island pop folk singer.”

“People really respond to that,” said Shapiro, who also serves as artistic director of the Cecilia Chorus of New York and Cantori New York, which performs new and lesser known works for vocal ensemble. He has won the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers’ (ASCAP) award for programming six times, with three different ensembles.

That kind of imagination, versatility and depth has also led him to conduct operas with The Juilliard School and several opera companies; and to teach at Juilliard and the Mannes School of Music, the Teachers College at Columbia University and a summer conducting program in France.

He sees conducting and music generally as problem solving, rather like the New York Times Sunday crossword puzzle he polishes off within 50 minutes. “There’s an analytic side and an expressive side,” he said.

He may have inherited some of each. Shapiro grew up in New York, the son of an electromechanical engineer who played the clarinet and guitar and exposed him to both classical and folk music.

“One thing I remember people saying about my father is that he could look at a motor and rotate it in his mind,” he said.

A cherished remnant of his grandfather, Rabbi Isaac Shapiro, survives on Soundcloud (under Mark Shapiro), three cantorial songs starting with the brooding Hineni (Hebrew for “Here I am”) a rumination for High Holidays sung in a rich lower tenor or high baritone.

He attributes some of his eclecticism to his maternal grandparents, Holocaust survivors who hid with their children (Shapiro’s mother and aunt) during World War II before emigrating to the United States from Europe.

“What is the latest dance? What are people reading?” Shapiro said. “I think I got that gene.”

He studied piano growing up, a skill that has helped him in all aspects of exploring music. After graduating summa cum laude from Yale University, he headed to France “to explore the world and myself.”

He studied at the École Normale de Musique in Paris and taught at conservatories in Boulogne-Billancourt and Châtillon, which named him an honorary citizen. For several years he was Assistant to the Director at the Conservatoire Américain de Fontainebleau. He would later do graduate work at Johns Hopkins University’s Peabody Conservatory en route to a doctorate at Stony Brook University.

The European sojourn left him fluent in French and improved his German and Italian. He reads at least one book in each language every year. That trip wasn’t the only significant life event that started with an instinct.

For example, he hates road trips but took one with husband Rian to Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia. “One thing led to another and we bought a cabin on the remote part of the island,” he said.

A chance introduction to a cellist at a nearby resort led to a conducting gig with the Halifax chamber orchestra Nova Sinfonia, where several of the musicians told him the Prince Edward Island Symphony was looking for a music director. He auditioned and got the job.

In the early 1990s, he plucked a book at random off a shelf of the New York Public Library: Mass in D, by Ethel Smyth. Taken by the arresting D minor opening, he looked up the British composer. After its 1893 premiere at the Royal Albert Hall, George Bernard Shaw wrote that a new era for women composers had arrived.

He got it into the program for the Monmouth Civic Chorus, which performed the U.S. East Coast premiere on Jan. 23, 1993. Twenty years later, Shapiro brought the work to New York for the first time, a performance by the Cecilia Chorus on April 14, 2013.

The composer, now known as Dame Ethel Smyth, was “really smart and bullshit-free,” Shapiro said. He admires the second attribute as much as the first. He believes in starting rehearsals on time and with a minimum of fluff.

“I’ll tell a funny story if I can get it done quickly,” he said, “but otherwise I think bullshit-free is the way to go.”

Maybe it was Shapiro’s analytical side that came to the rescue last year, when Encompass Opera needed an emergency conductor. Shapiro attended some rehearsals of Anna Christie, an adaptation of a Eugene O’Neill play, but had never conducted the orchestra until the performance.

“It went very well, everybody was very happy,” he said. “So I think I have a lot of passion in my music making, but I’m a pretty cool cucumber in those kinds of situations.”

His intuitive side monitors the energy level and quality of the musicians performing under his baton. From Gustav Meier, an internationally acclaimed conductor who directed the conducting program at the Peabody Institute, he learned not to force the action.

“What he said was, ‘If it gets boring, stop conducting,’” Shapiro said, an instruction that meant, “Get out of the way.”

He makes the end result sound easy or at least achievable, even though for most it is neither.

“We know that the brain is a massive parallel processor,” he said, “the same way we can drive and talk (simultaneously). You become hyper focused on this or that thing, but also really tap into the brain’s ability to see the big picture and the details concurrently. So it’s never one or the other, and you’re able to jump in and out of that.”

– Andrew Meacham