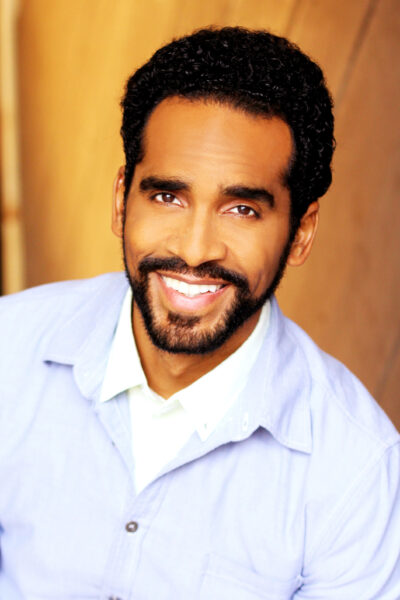

Finding connection: A conversation with Edward Elwyn Jones

Edward Elwyn Jones grew up in a choir, learning new music every week at the Cathedral School in Llandaff, Wales, an experience that shaped his career as one of music’s most versatile conductors. He began singing at age 9, adapting to the demands of a boy choir that sang at a professional level, under the baton of a strict conductor.

Now Jones thinks that rigor was necessary to corral some of his classmates, boys who would rather have been outside playing soccer. But he favors a more genial style himself, believing that the same tactics that whip some students into shape may repress others.

“That’s a really difficult thing psychologically, because not everyone responds the same way, either as a musician or a human being,” he says. “You have to try and gauge the sense of a room. I strongly believe that people make their best music when they are comfortable and when they are enjoying what they do.”

As a boy, Jones found himself bored on all-day car trips with his father, a buyer for the gift shops at historic monuments throughout Wales. He would later learn about the choral tradition that developed in those medieval castles, unaccompanied voices singing lyric poetry in harmony. By high school he was playing the organ, harpsichord, piano and trumpet.

Later, Jones’ professors put him in charge of the chapel music program for all four years at Emmanuel College, Cambridge University, a job he found “amazing, and almost criminal at the same time to hand over this amazing choir to someone so young and inexperienced.”

He studied art history and world history, literature and music with equal curiosity, and came to see his courses as one interrelated field. History also deepened his appreciation for music. He was fascinated by influences in the lives of composers, including some that remain unknown.

“People know that Mozart traveled a lot when he was younger, and later in life as well,” he says. “But he actually spent 15 months in London when he was 8 years old. And just thinking about what he was listening to there, what operas he was going to see and how that informs what he then goes on to write — to me it’s very interesting.”

He hears a bit of Salieri in Mozart’s Cosi fan tutte and Don Giovanni, of Beethoven in Brahms and Schubert, and Donizetti in Wagner. “And you see then how these pieces can get put into context, that they don’t just appear out of nowhere, that they really do come from a long line,” he says.

The same connections exist between music and other disciplines. “I think it’s difficult to become a musician without having any sense of what was going on at the same time in art history and literature. Usually, those disciplines precede musicby a couple of decades. Music often is a little bit late to the game in the sense of changing styles. So it’s interesting to see what’s going on in terms of literary techniques, or in terms of art history techniques.”

He tried to apply that versatility at the Mannes College of Music in New York, where he earned a master’s degree. But his mentors rejected Jones’ proposal to build his degree around conducting chorus, orchestra and opera.

Choose one, they said. He picked orchestra. He also assisted a Metropolitan Opera conductor and worked with church choirs. Learning to conduct across all three helped him immeasurably, something he wishes more colleges that force specialization would appreciate.

“I don’t think it is a brilliant way of encouraging good conducting across the board,” he says. “You see a lot of good orchestral conductors who really get in a bit of a pickle when they try to conduct a choir, and similarly, a lot of choral conductors who are derided by orchestras when they stand up in front of them because they are somewhat different skill sets.”

Jones also has a thing or two to say about the most critical relationship of all, between musicians and the audience. If great musical art forms are to stay alive, it wouldn’t kill them to loosen up a bit, he maintains.

“We are expecting audiences who have been working all day—and presumably have to work the next day—to go to a theater at 7 o’clock and watch four-and-a-half hours of a Handel opera in silence, in the dark, in this reverential tone. In Handel’s day, what was going on onstage was almost a side show. They were talking, they were playing cards, they were looking at each other. People were just wandering around chatting. We’ve lost a kind of very immediate connection between the audience and the stage.”

Jones lives in the Boston area, where he enjoys museums and spending time with his sons, Henry and George. On his next visit to Wales, a castle or two might be on the itinerary. No doubt he would narrate the same historical attractions that once bored him in the same fluid authoritative style with which he can speak on many subjects.

It is only when he is asked a personal question – about what brings him joy – that he pauses.

“Apart from my kids, I think my greatest joy comes from making music,” he says. “It sounds cheesy, but whatever music I’m making at that particular time – while I’m in the moment with the music – there is just something special about that. I can’t really put it to words, and I’m not sure I want it put into words, either. I think the words add a layer that confuses it.

“It’s just a very special feeling that I think most musicians share. We are bound by that great love of music. And when we can find that, find that special place, that’s a unique thing.”