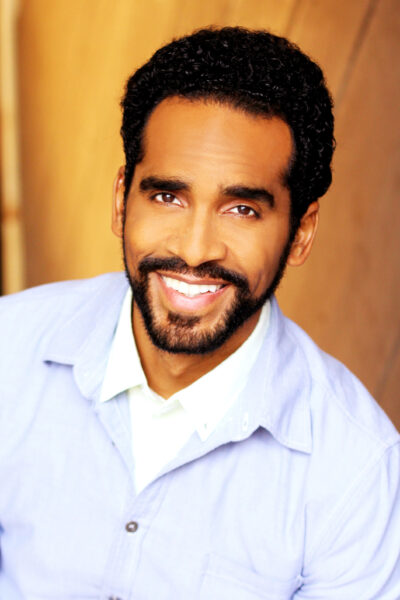

Ann McMahon Quintero: Digging deeper, she found her true voice.

Ann Quintero might not have entered the Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions, a critical step in the success of the some of the country’s most important opera singers. A 21-year-old senior at Northwestern University, she had never been to New York.

But there she was, urged to enter by her voice teacher, wearing a dress her mother had made. The mezzo-soprano described the experience as amazing and a bit bewildering. Her family had supported her in music but were not themselves musical.

“I didn’t have a true sense of the context.” Quintero said. As she moved up through successive rounds, she felt sure there had been some kind of mistake.

Soprano Twyla Robinson, who won that year, told her mother not to worry. “You have to understand,” she said, “she’s just a baby.” Quintero went on to work with the Washington National Opera and win multiple competitions, earning critical praise for her pure mellifluous sound and acting chops. She relished the complicated Verdi roles of Amneris in Aida and Azucena in Il Trovatore, zeroing in on the flaws that make them relatable.

“There is no such thing as a pure villain,” said Quintero. “When you look inside them, they have their reasons for everything they do. If you have compassion for them, you can understand them.”

Similar themes have been on her mind in recent performances of the Verdi’s Requiem, part of a world tour of the Defiant Requiem Foundation. Holocaust survivors have appeared at tour stops, a poignant reminder of prisoners who performed the requiem in a Terazin concentration camp their Nazi captors had hastily cleaned up for visitors.

The inmates intended the cataclysmic finale (Libera me, Domine, de morte aeterna) as a coded plea for help which literally means “Save me, O Lord, from eternal death.” The visitors, whose number in 1944 included a delegation of the International Red Cross, tragically failed to pick up on the hint.

Their message remains critical today, Quintero said, in an increasingly acrimonious world climate. “As we are losing eyewitnesses, we’re losing those who can put a personal face on that genocide as an immediate human reality,” she said. “We think of it more as a concept. And this is, I think, extremely problematic – to see what prejudice and politics and fear mongering can do.”

Quintero grew up in the Chicago area, the daughter of a physician from El Salvador and a straight-talking nurse from an Irish neighborhood on Chicago’s south side.

“They still don’t really understand what I do, and that’s okay.”

She played stringed instruments and underwent the rigors of Irish dancing until early adolescence. She performed in plays and musicals, including work at the Steppenwolf Theatre and Chicago’s Second City.

“Pretty much through college, I always considered myself an actor who could sing,” she said. The difference between theater and opera, she observes, lies in part in the grander size and scale of the latter.

“if you have 250 seats or fewer, micro expressions are great,” she said. “If you have 2,000, the people in the nosebleed seats aren’t getting it. It has to be slower, larger, simpler.”

She performed across the United States and Europe, at times undergoing changes and reflections. For a while during the 2007 recession, she wondered if she wanted to continue singing.

“My friends said, ‘You can’t quit, you can’t quit,’” she recalled. Around that time, she reconnected with an old friend. Robinson, the National Council winner who had gone on to a stellar career, had a different take.

“She said, ‘You do what you need to do. But you’re still beautiful and you’re still valuable and you’re still my friend whether you keep singing or not.’

Paradoxically, the permission not to sing strengthened her voice. She listened to some of her own early recordings and heard an expressiveness that surprised her.

“We live in a society that can punish enthusiasm and mistakes, especially in the classical music industry,” she said. “There is such a focus on flawlessness and not being offensive. And you work so hard on not being offensive that you end up not being interesting.”

Hints of that forgotten joy began to re-emerge. Once, during a Reiki breathing session, she found herself thinking about Sesame Street muppets Bert and Ernie.

“As a child, I absolutely aligned myself with Ernie,” she said. “There is this chaotic good, this joyful mischief, an energy and enthusiasm. And over the years — it’s a little bit the business and it’s a little bit just life — I became a Bert. I was concerned about my bottle caps, my paperclips. Keeping everything neat and tidy. I decided to reawaken my inner Ernie.”

She cooked healthy foods, wore red lipstick, something her mother considered unnecessary, sang at Marie’s Crisis Café in Greenwich Village.

“I started doing unnecessary but bold and vibrant and beautiful things,” she said.

A sense of hard-won inner freedom came with an additional benefit: “It also helped me to unlock the true size of my voice.”

Once, a colleague praised her tenacity, a compliment she found surprising.

“I never thought of myself as particularly tenacious,” she said. “Stubborn, maybe. I always just assumed that’s sort of what you do. That might be something I picked up from dancing. You get injured, you mess up, you fall down, whatever. You get up and you do it again.”