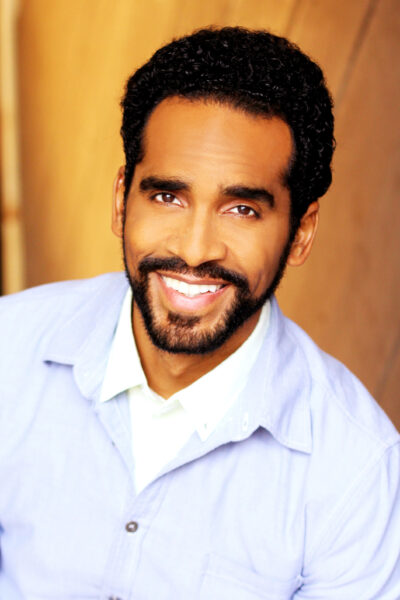

Getting one of the music world’s top honors took Athlone Artists’ Karim Sulayman by surprise. Just making it to the Staples Center in 2019 had already surpassed his expectations for his first solo album, Songs of Orpheus, recorded with the premier Baroque ensemble Apollo’s Fire.

The nomination deeply pleased Sulayman, a Lebanese-American tenor whose silky highs and textured lows earned raved reviews. It meant someone had taken the time to really listen. But a Grammy win?

“I thought I was going to a fun party and would meet some fun people,” Sulayman said. “As passionate about this music and as proud of this album as I am, I didn’t expect my first solo disc, of this specialized repertoire in particular, would penetrate the mainstream the way it did.”

Then Sulayman and Apollo’s Fire won the Grammy for Best Classical Solo Vocal Album. That likely could not have happened without Sulayman’s haunting lyrical interpretations of a dozen songs by Claudio Monteverdi and his Italian contemporaries, 16th– and 17th-century poets and musicians who dreamed of capturing the spirit of ancient Greece.

Sulayman was born in Chicago, the son of a pediatrician and his wife who left Beirut during the Lebanese Civil War. At age 3 he saw a violin and told his parents he wanted to play it. While he studied violin for 11 years, the Chicago Children’s Choir laid a roadmap to his future.

Indirectly, at least, the choir might even have given him advance training on a rare ability – a range that glides smoothly from high baritone to near countertenor. Sulayman’s voice did not change until around age 16. Before that he sang alto, soloing with the Chicago and St. Louis symphony orchestras and the Chicago Lyric Opera.

“There was a long time when I was singing in a completely different range,” he said.

Later on, he said, “I did a lot of high French Baroque tenor stuff where I had to learn to maintain a very high tessitura through the course of the night. It was very hard work, but helpful in accessing my high notes and smoothing out the passaggios and all of that so that everything sounded like a piece.”

Living his childhood dream more or less fits his personality, if you believe the Myers-Briggs test. The inventory rated Sulayman an ENFP, which is sort of an intuitive extrovert who trusts his emotional barometer and tries not to judge others.

“It kind of nailed me because I do like being with people,” he said. “I like holding a room. But I absolutely value my alone time and need to recharge.”

He likes helping composers flesh out new music. “It’s important to always think forward,” he said. “Otherwise we’ll be extinct.”

Late in 2016, Sulayman did something no introvert would consider and which may live forever on the Internet. He stood, blindfolded and holding a sign, on a sidewalk near New York’s Central Park.

“Hello, my name is Karim and I am an Arab-American,” the sign read in part. “Like many people who are Black, Brown, women, LGBTQIA, Latinx, Muslim, Jewish, immigrants and other, I am very scared. We are anxious and uneasy in our own country…”

Before and after that day, videos of similar “blindfolded Muslim” social experiments had been posted online from North America and Europe. In all, a lone man or woman would invite strangers to approach for a hug.

“There were a lot of people just not listening to each other, within the left and the right,” Sulayman said. “And what I think is missing is a real dialogue without people shouting at each other.”

Even so, Sulayman staged his experiment across the street from a Trump International Hotel and Tower, a flashpoint of left-right division. He had already held similar blindfold experiments in Chicago and Houston, also adjacent Trump properties.

His sign closed with an offer to connect through a handshake, a hug or a selfie. A lot of people kept on walking. A few called him names, but many just stopped. They read the sign and studied the bearded, blindfolded man and each other. Then they drew closer and embraced him, some fully and some cautiously.

“Some people were really holding on and saying amazing things like, ‘This kind of togetherness is exactly what we need right now,’” said Sulayman, who hugged strangers he could not see for five hours.

A viral video captured New Yorkers exchanging words and hugs with Sulayman, overlaid with his voice singing all four parts of Sinead O’Connor’s In This Heart.

Songs of Orpheuscame out a year and a half later, about a spellbinding musician who went to hell and back for love. In song lyrics or actions, that’s what Sulayman says he’ll keep doing.

“I think I’ve been on a path and it feels clear to me to stay on this path,” he said. “And I do feel like I’m supposed to sing, and I’m supposed to use my voice in a lot of different ways.”