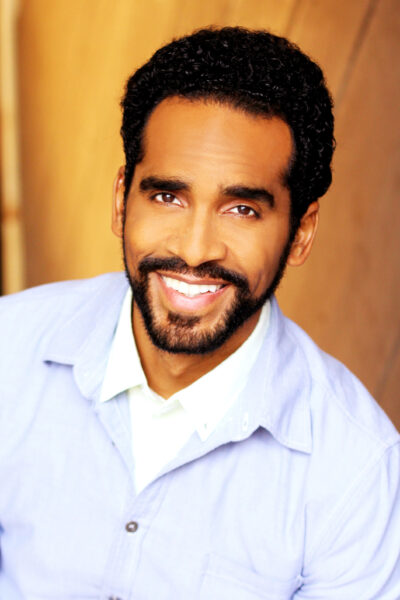

He might be one of opera’s most genial directors, the kind who asks a lot of questions and wants to stretch singers within their limits. Certainly Gianni Santucci, already a respected choreographer in dance, opera and film, counts as one of the most versatile. The quality he exudes most, a seemingly inexhaustible well of patience, masks a strict work ethic grounded in preparation for each scene before the first rehearsal.

He strives to achieve the “total theatre,” a concept best known from Wagner operas in which music, voice, movement and spectacle combine for a unified work of art. To get there, Santucci relies on his own brand of communication, a talent he has refined into its own art form. Each connection with a singer or dancer or lighting technician gets him closer to that goal, the experience he wants for the audience. After decades traveling the world, the Italian director is settling into a new phase in New York, ready to help opera performers bring out their best.

“You need to really understand what people can do and try to find the meaning of every movement they have to do,” Santucci said. “Because for the dancers, the movement is the meaning. For the opera singers and the actors, what they are saying is the meaning, not the movement. So you need to approach yourself in a different way, and you need to express your wishes in a different way.”

So consumed with messaging was Santucci during a rehearsal of La Traviata, he worked with the two principals on a single scene for four hours. In the second act garden scene, with the Amami, Alfredo aria sung by the legendary Mariella Devia as Violetta to Germont, a fitting physical expression was needed to match the moment, a farewell which only Violetta knew would be permanent.

“So the point was, should they stay close to each other?” Santucci said. “Should they touch hands to say goodbye, or should they be away one from one another to make that statement?”

The couple expanded to the exits and contracted again, feeling the tension but never quite closing the distance for fear of further heartbreak.

“When you are talking about lovers, two feet away is an immensity,” Santucci said. “You want to touch your lover. But in this case, two feet apart was the closest they could get.”

Santucci was born in Arezzo, Italy. Gymnastics took him away from home even as a child, training to compete at the elite level. He won a national championship in the rings event, then trained Yuri Chechi, eager to learn, to win five consecutive world titles on the rings and a gold medal in the 1996 Atlanta Olympics.

A major turning point came in the early 1980s, when Santucci danced for an Italian television show that was also filmed and broadcast in the United States. From 1984 to 1992, he danced in ballet and modern dance companies while pursuing what was becoming his first love, designing dance productions. Later on, he assisted a novice director in an operetta he already knew, a role that expanded into directing opera.

He said he respects singers’ needs in producing sound while also aiming for maximum clarity of expression. “You tell them what you would love to see and what you would love to have,” he said. “And they will tell you what they can do. Even if they don’t express it loudly, with their bodies they are telling you what they can do.”

He has stayed in film, too, helping Liam Neeson pull off a dance scene in a Paris nightclub in Third Person, a romantic thriller, and staging Pagliacci within Woody Allen’s To Rome with Love, a short-lived comedy about an opera director.

These days, most of his work comes down to directing or choreographing shows. And while he had enjoyed choosing which art form to direct and traveling to Japan or the Middle East, two recent developments have him likely to stay in the U.S.: The arrival of his Green card and his signing with Athlone Artists.

“Being part of a great artists’ company,” he said, “it’s not just a place. It opens up possibilities. My next step will be to do operas here in the United States.”

He wants to bring a flavor of his homeland to the U.S. “I know many directors already came to the States, but they normally come for the production,” he said. “They don’t live here. So living here and being part of the city every day, I am learning more and can share more of myself.”

At the end of every successful show comes another moment he lives for, those cheers that tell a cast that all of those messages he was trying to deliver got through.

“The applause of the audience is what you’re looking for. That’s the point. To see people understand your point of view from your hard work, and the fact that you have done your best. That is the reward that is truly priceless.”