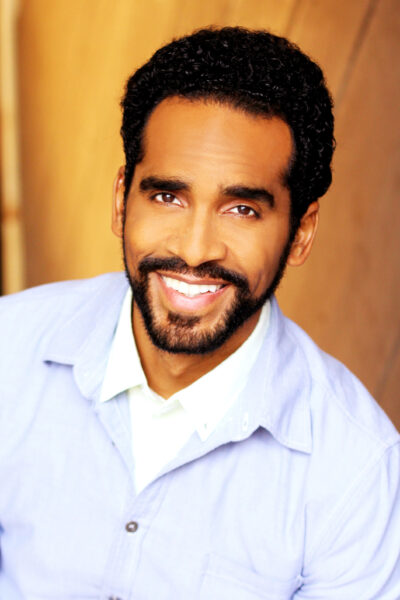

Chuck Hudson grew up training as a gymnast, in which every move leads to the next. Maybe that’s why he didn’t lose his balance when Marcel Marceau, the mime he had revered since childhood, disrupted his plans and changed the course of his life.

Today a growing number of opera performers and theaters are seeking out Hudson’s services as a director. It might seem odd that he would attribute so much of that demand, and draw the core of his teaching, from his work with Marceau, since he embarked on that course of study with the theater in mind, not opera.

His website delivers the Hudson message in a variety of ways. A singer in a testimonial talks about learning to sing a passage with conviction after taking an acting note. Training brochures advise that the opera world is changing, that the body should be considered an instrument as well as the voice.

Today he directs operas and conducts master classes in theater and opera on three continents. His emphasis on acting and movement integrated well with an increasingly competitive opera scene, and is coming not a moment too soon, he believes.

“Singers want it, producers want it, conductors want it, audiences want it,” he said.

Hudson spent his early years in Stamford, Conn. before his father’s career in the oil industry led the family to Houston. There he continued to compete in gymnastics and to deepen his interest in Shakespeare, Joseph Campbell and musical theater, topics that led him to favor the University of Houston-School of Theater over Princeton, which had also accepted him. There he would add to his love of languages, study classical and contemporary acting, Shakespeare and French absurdism while also juggling a mime group and fencing practice.

Somehow, all of that chaos served up a divine coincidence. Hudson’s fencing coach happened to be a colleague of Marceau’s, an international star since the mid-1950s. Unbeknownst to Hudson, he snuck Marceau into the theater when Hudson’s physical theater company performed. After the show, the coach introduced Hudson to the legendary artist often seen as a silent white-faced storyteller who sometimes wore a stovepipe hat and carried a red flower.

“And Marceau said, ‘What are you doing when you graduate college?’” Hudson recalled. “I said, ‘I’m going to move to L.A. and be a movie star!’ like every actor is going to be. He said, ‘Well, if you’d be interested in studying with me, I just saw your audition, and you can come and study at my school.’ And that just fell in my lap. I’d be a fool to say no.”

Hudson earned the equivalent of a Masters of Fine Arts in Dramatic Corporeal Studies in Marceau’s École Internationale de Mimodrame de Paris, the second American to do so.

“Working with him was astounding,” Hudson said. “This is a man who – for all intents and purposes – had invented an art form.”

Marceau gave criticism in laserlike notes, and one suggestion might take five weeks to resolve before it rang true on stage. Back in the United States, Hudson worked as a teacher and director. The Seattle Opera asked him to create and implement a movement and acting curriculum for singers, and to direct productions. He accepted, a decision that ultimately led to his current operatic career. In all situations, he found that he was taking the principles he had learned from the Marceau school into his work.

“Something that Marceau always said was that he would do that same show in South America, in Asia, in the United States,” Hudson said. “And the people would laugh at the same things, they would cry at the same things, they would be hushed by the same thing, because he found this universal human behavior that spoke to everyone. And he said his art was closer to the art of music because music does the same thing.

“So when I’m staging an opera, I’m approaching it from that same physical standpoint. I want the human behavior up there to represent what people would do rather than relying on looking at supertitles to try and understand what’s happening between two singers.”

As for operatic performers, Hudson said he’s not looking for opera singers to become movie or stage actors.

“You’re not trying to make it look like a movie because it’s not a movie that you’re doing,” he said.“Opera demands that we perform some things that cannot happen in reality but that are truthful in the context of operatic performance, calling for something different from the realism of a spoken play or the naturalism of a film. Desdemona sings for six minutes and dies of asphyxiation because this is ‘Theatrical Truth’ in Verdi’s Otello.

“You’ve got to find the dramatic truth in that and not the reality in that. That’s what death sounds like in Verdi.”

Asked about the surprises in his life, Hudson said they havenever stopped.

“I thought I was going to be a speaking actor. Wound up working with Marcel Marceau…There are things that come into your path completely unexpectedly. And especially if you are challenged by them, I believe you should say yes to them and see what happens.”