Why settle for just one musical style if you can excel in many?

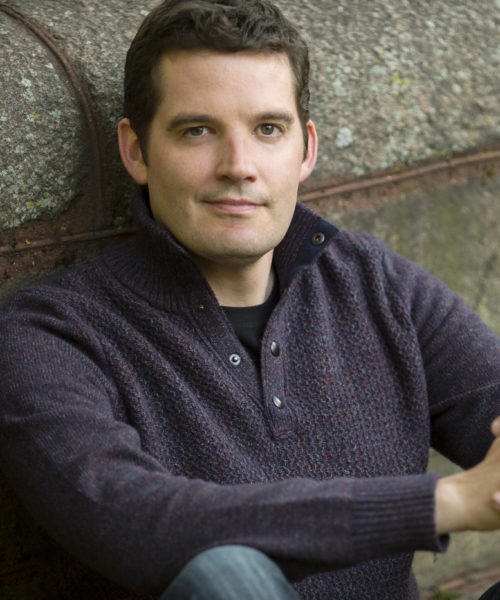

A week before the opening of Dido and Aeneas, baritone David McFerrin was excited, and not just because he would be reprising his first operatic role (Aeneas) that he first played at the Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music.

The Henry Purcell opera, set to open and close March 29 and 31, 2019 in Boston, includes a March 30 date at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. A love story between the Queen of Carthage and the Prince of Troy would play out at the Temple of Dendur, an actual ancient Egyptian monument commissioned by the Roman Emperor Augustus and erected in 15 B.C.

McFerrin said he was looking forward to performing with period musicians in the Handel and Haydn Society, part of the Boston classical music scene he so cherishes, led by acclaimed English conductor Harry Christophers.

“They are the cream of the crop,” said McFerrin, who has lived in Boston most of his adult life. “I know from an artistic level it will be top-notch.”

Additional staging by Aiden Lang, the Seattle Opera’s general director, added anticipation to the Metropolitan performance, expected to be livestreamed by thousands.

Being cast in Dido promised an artistic peak experience, the kind he lives for.

“My favorite aspect of this career,” he said, “is the collaborative element, putting things together as part of a team.”

Such experiences remind him of playing Ultimate Frisbee on a nationally ranked team for Carleton College. In each, skilled performers attuned to each other’s tendencies sprint or feint or dive to advance an elusive floating something.

McFerrin, who also played baseball, basketball and soccer growing up, said he prized both the camaraderie and personal commitment required of team sports. “And when I’m able to find it, there’s a similar attraction to music making — to take individual talents and skills and coalesce them into a sum that’s more than its parts.”

He left the Ultimate Frisbee team after a year because it conflicted with his vocal studies. He retained an interest in political economy, an academic concentration that encompasses economics, politics, trade, philosophy, history and culture.

“It’s not every day you see someone who is majoring in musical performance devoting an almost equal amount of time to politics and international relations,” he said. “But those were my major interests.”

Mentors advised McFerrin which of his many talents should guide him, and how.

“I got a lot of advice from different people,” he said. “But I think for the most part I’ve had to figure it out on my own.”

His voice could swell from moody depths to bright and rapierlike, dancing along a melody like a tenor lead. That made him special, if not easy to pigeonhole.

“In the arts in general, it’s easier to highlight excellence when people focus on one area,” he said. “So it has been a challenge to pursue different genres and repertoire. And one could consider it a fault. But after having done this for 20 years, I’ve come to see it as a strength. To be who I am.”

On a musical menu crowded with contemporary opera and the eternal favorites, Baroque music and popular, lyric opera or chorus work or the American songbook, McFerrin chose all of the above. Only his passion connected these disparate threads.

“You have to find your strength to make it in your career,” he said. “For some people, it’s to be known as the quintessential Verdi baritone or Bach soprano. That’s not where I have ended up, and the way that I identify myself is that I am able to switch from doing a show with the Boston Pops to Renaissance to Baroque opera and do that successfully.

“It’s also my passion. I love the variety. Each style of music uses different skills that call on different interests and different aspects of my personality.”

He has relished under-appreciated works, posting a finale in the title role of Eugene Onegin and a song from the musical Love Life on his website, both carried off with dramatic intensity and a touch of humor.

“It’s all storytelling when you come down to it,” he said days after finishing a run with the Boston Lyric Opera of The Rape of Lucretia, Britten’s seldom-heard chamber opera. In this one, McFerrin noted, theatre director Sarna Lapine had performers singing throughout the hall, coming toward or from a circular stage.

“For the people who are able to see these stage productions, I think they have universal appeal.”

For those in smaller areas who don’t, he said, “That’s a question we all struggle with, how to keep classical performance alive, and not just in certain centers. I don’t have the answers. But I’m interested in contributing to getting this work done.”

McFerrin grew up in Western Massachusetts, the son of an African studies professor and a choral director. When he was 14, his parents’ work led the family to Ghana for a year.

“It was a very different part of the world, a different way of living: my first experience as a racial minority, and exposure to stark economic disparity and my numerous comparative privileges” he recalled. “It was eye opening in so many ways. I came back from that experience fascinated by and eager to engage with the entire world.”

He returned in college, this time to South Africa, to study the political impacts of African choral groups during Apartheid. He thought about going to graduate school in international relations — and might have gone, had he not been accepted into Brevard Music Center, a North Carolina summer opera program.

In down time, McFerrin enjoys hiking, cycling, and cooking and traveling with Erin, his wife. A historical preservationist, she attends his concerts when she can.

“She provides genuinely honest feedback about my performances,” he said. “At least for me, it’s vital to have a life away from the music world.”

The family has had a new focus since August 2018, when daughter Fiona was born.

That’s given David McFerrin something else to think about.

“I’m thinking a lot about the world we’re bringing her up in, and am committed to improving it,” he said.

In the meantime, he waits to see where his music will take him next. “I’m excited to see what the future holds for me as a performer,” he said. “I’m open to new opportunities, new genres that I haven’t yet explored.”